BY: Nada AlNaggar

@NadaWahba10

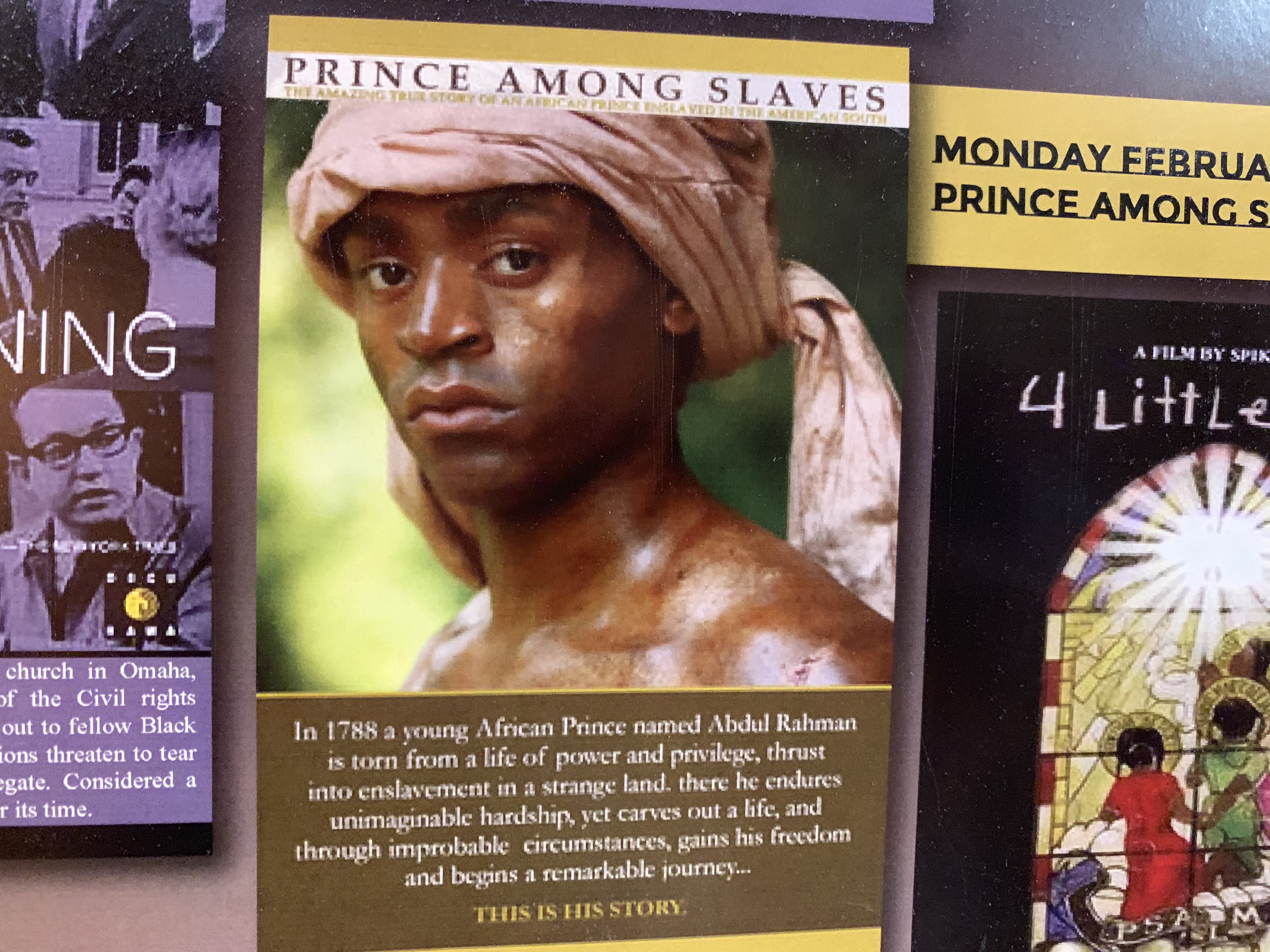

The second series of the Black History Month movie screenings showed Prince Among Slaves, a historical documentary highlighting racial discrimination and slavery as seen through the eyes of an African Muslim prince abducted from his home in West Africa.

Torn from his family, his wife and his son, Prince Ibrahim Abdulrahman was captured at the age of 26 and lived the life of a slave for 40 years until he was eventually released.

The 2006 film adapted from a book of the same name by Terry Alford shows Abdulrahman with other African prisoners held in a makeshift prison aboard an English slave ship where they were chained, deprived of food and water, and beaten as they traveled across the Atlantic Ocean.

It would be a perilous trip aboard the English slave ship as dozens would die of disease and malnourishment; their corpses thrown into the sea.

Abdulrahman, however, survived and arrived in Mississippi in 1788, only to be sold into bondage to white plantation owner Colonel Thomas Foster.

Abdulrahman pleads with Foster that he is an African prince whose family would pay gold for his return, but the plantation owner scoffs at him incredulously.

It is here that the film works brilliantly to highlight racial discrimination that ran parallel with the slave trade, and the disregard of the West towards the rich cultures of Africa.

Despite clearly being educated, Abdulrahman was stripped of title and status and toiled as a slave..

“He paid no attention to my words except to mock me, and from that time, he called me Prince,” Abdulrahman narrated.

When one of Abdulrahman’s friends from West Africa arrived in Mississippi and confirm his lineage, Foster remains in denial and refuses to let him go. This is one of many signs of white greed and prejudice in the film.

“You’re telling me my prince is an actual prince?” Foster sarcastically exclaimed.

The racial prejudices of slavery had been deeply ingrained in America for hundreds of years by the time Abdulrahman reached its shores, and the currency of value for the West was an African slave.

“There was an insatiable demand for slavery,” said the film’s narrator Yasiin bey, also known as Mos Def.

As the years wear on, Abdulrahman marries the slave girl Isabella and fathers nine children, all born into slavery. They started helping out on the plantation as soon as they came of age.

“As a political theorist, I am interested in questions of statuses. In other words, is there such a status as a free person as opposed to an enslaved person? If you have free people, how free are they?” said Chris Barker, assistant professor of Political Science.

Parker further explained that in the movie, Africans were not protected under any law, even if it were a matrimonial one, which goes to show how they were deprived of basic rights. In other words, the law did not apply to them.

After petitioning the US government, Abdulrahman is allowed to travel back to Africa but is forced to pledge to return; he is made to leave his new family behind.

“The married couple could be separated. Their children could be separated from them. So, in other words, what we see in the movie is a blunt racial category; African vs white,” Parker elaborated.

Mahmoud El Hakim, an English and Comparative Literature and economics junior and one of the audience members at the screening, says he was moved by the indignity forced on African Americans at the time.

“This particular movie is different in the sense that it basically shows how the torture of slavery was not merely inflicted as physical pain and labor, it was inhumanity and alienation; a systematic disenfranchisement of a whole human race. Ironically though, it is a rare story of someone who made it out,” El Hakim said.

El Hakim was just one of a handful of students who attended the screening.

When asked about the reason behind such a small number of viewers, Assistant Professor of the History Department Mark Deets, said some students might feel uncomfortable about the subject matter.

“Because people know how inhumane and immoral it was,” he said.

Deets thinks it is very crucial for university students, especially at AUC, to have a background on the history of slavery and be able to compare and contrast between modern forms of slavery and other forms that previously existed.

“I think developing a historical consciousness for these stories of people’s experiences and the diversity of experiences is imperative. We should continue to talk about this history to show how American culture, economic and political power comes from this history,” he added.