From Cairo to Jerusalem: The Ongoing Catastrophe of 1948

By Mariam Ismail

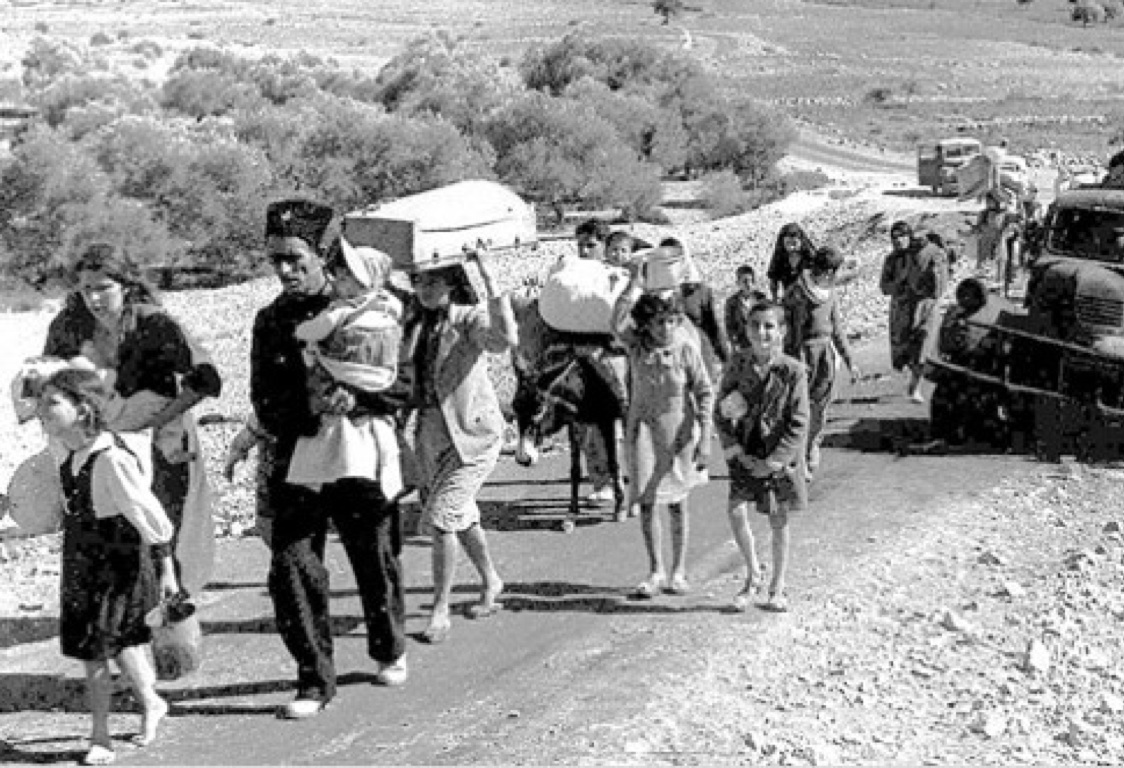

Assistant Professor of Law Mai Taha last week offered a rather novel analysis of the more hidden colonialist decision-making behind the mass exodus of Palestinian refugees in 1948, commonly known as El Nakba (The Catastrophe).

During her lecture “From Cairo to Jerusalem: The Ongoing Catastrophe of Law and the Laboring Female Body,” Taha said that she was not looking at the exodus from a gender studies approach but focused on the Nakba, in a way that encompasses its movement from Cairo to Jerusalem in the 1930s and 40s.

“In the process, I look at the small and large legal decisions and questions pertaining to the construction of gender, race and class,” said Taha.

She began her talk by drawing a stick figure of a man with a top hat.

An arrow pointing in his direction identifies him as R.M. Graves. From there, the rest of the presentation revolves around the man’s colonial career from Egypt to Palestine.

“The history of international law and its relationship with colonialism has often been studied by scholars,” said Taha.

“However, his story brings to bear how international legal institutions, namely the International Labor Organization (ILO), the League of Nations and later the United Nations, in the 1930s and 40s, consistently sought to govern the details of life of colonial people in the Middle East through experts,” added Taha.

In an intricate play of intersectionality, Graves is revealed to be a combination of the white-male-colonizer who is given authoritative positions over fundamental organizations that shape a country’s structure and dynamics.

His high-ranking functions enabled him to change laws in Egypt and Jerusalem, and Taha explained how these minor adjustments built up to major consequences, namely, the Nakba.

After serving as the Director of the Egyptian Labor Office, he ended up having to resign due to increasing Egyptia nization and moved to his final posting as Director of the

Palestinian Labor Office. From then on, he was considered “a colonial expert”.

“I am interested in how international law was implicated in governing the material details of life from mundane specifics such as the number of municipal workers sweeping the streets of Jerusalem to the governing of red light districts in Cairo, for example, to the large events; from the slow and fast partitioning of Palestine, and finally to the 1948 Nakba,” Taha said.

In this new position, Graves began enforcing continuous inspections in workplaces, carried out by “white- colonizers” now in places of authority.

His policies induced a shift in Jerusalem’s power structure and created a culture of inequality: a detailed government structure and legal procedures that construct class, gender, and ethno-national relations between the various subjects.

Taha revealed that although Graves was often emotional and occasionally patriotic to Cairo and Jerusalem, the legal decisions he made eventually formulated the governance of the Middle East in the interwar period.

“Although, the Nakba was documented in Israeli history as a non-legal event, it was slowly occurring through the thousands of small legal decisions before, during and after the actual events of the Nakba. It was occurring through all of the legality of that catastrophe,” said Taha.

By this token, Taha removes the temporality of the event by connecting the past, present, and future; the Nakba is ongoing, and limitless. It did not start in 1948 nor did it end with the creation of the Israeli State.

“It is ongoing precisely because it continues to be the sum of its parts of the small and large legal decisions, from Graves’ labor policies on the employment of women, to his municipal orders, to the Palestine Mandate treaty, to the Partition Plan, to the hundreds of General Assembly and Security Council resolutions, and even to the celebrated Interntional Court of Justice’s Wall Decision,” she says, referring to an Advisory Opinion by the World Court, which pronounced the area as occupied territory and reaffirmed the Palestinians’ inherent right to self-determination.

“[The presentation] opened the idea of the Nakba as a collection of wrong decisions,” Assistant Professor of Political Science Nora Salem told The Caravan.