Egypt’s Future Journalism Culture will Face Hurdles

BY KANZY MAHMOUD

Media freedoms in Egypt began to move forward immediately following the January 2011 Revolution, raising hope that the fourth estate would begin to build transparency and accountability.

Since 2013, however, Egyptian media freedoms began to decline in the wake of increasing censorship and prosecution of reporters.

Egypt now ranks as the 6th worst jailer of journalists worldwide according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, an American nonprofit organization.

Earlier this year, a study published by the University of Erfurt (Germany) on the nature of Egyptian media said that in recent years “[Egypt] witnessed a roll-back towards Nasser-style authoritarian media”.

The media has become more polarized and less pluralist, the study added.

Challenges Facing Media Growth

Director and Professor of Practice at the AUC Kamal Adham Center for Television and Digital Journalism Hafez Al Mirazi told The Caravan that there are many constraints that hold back Egyptian media.

He believes that these constraints – which include political pressure, lack of funding and centralization – need to be changed to guarantee a more independent and free media environment in the country.

“It all depends on the political [atmosphere] in Egypt. If we have political freedom then you would expect the revival

of vibrant talk shows, [which] discuss real issues and not nonsense,” Al Mirazi said.

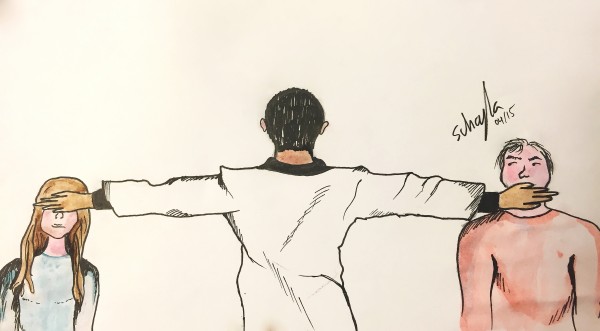

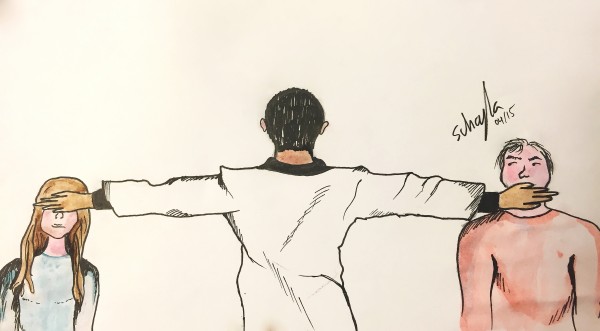

“Media are dealt [with] as dogs only, not watchdogs,” Al Mirazi added.

For that to change, Al Mirazi believes that the Egyptian political system needs to ‘mature’ and transform into a ‘real democracy’.

The Egyptian media is also held back by financial constraints. Advertising is the main source of income for different media outlets, whether broadcast or print.

The quality of news and information output can be compromised if broadcasters begin to sacrifice content for the sake of attracting more paying advertises.

“Those who have experience take shortcuts into what sells,” Mirazi said.

And what sells, according to Al Mirazi, is often “sleazy and exotic”.

Article 211 of Egypt’s 2014 Constitution stipulates that the Egyptian Supreme Council for the Regulation of Media is independently charged with the ‘regulation of the affairs of audio and visual media’ and monitoring the legality and funding of the sources of funding of the press.

Despite this, however, El Mirazi still believes that introducing a license for the practice of journalism would ensure that only qualified individuals are allowed to produce content for the masses.

Egypt also faces the problem of media centralization – meaning almost all production is localized in the capital.

Maspero – the headquarters of the Egyptian Radio and

Television Unit – and the Media Production City – where most Egyptian public frequency and private satellite channels originate – are both located in Cairo.

This leaves outlying provinces left to largely fend for themselves. With the absence of what

Al Mirazi calls “a real media infrastructure”, advertisers will continue to rely on a limited local base and focus on Cairo, and – to a lesser extent – Alexandria.

“[Decentralization] will dismantle this monopoly of advertising and give power to local places,” Al Mirazi said.

The Media and the State

Much of the Egyptian media’s relationship with the state came about as a result of the late President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s nationalization of the press.

This allowed the State Information Service to own or oversees most of Egypt’s print media.

Amal AbdelSalam, managing editor of Al-Akhbar newspaper, said “the government should never interfere in journalism or media unless in times of danger.”

El Mirazi stressed that there has to be an independent regulatory body similar to the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that lists rules and procedures for media outlets to follow.

In late 2014, editors-in-chief of several print and television outlets announced the formation of a broadcast media chamber tasked with formulating guidelines for the practice of journalism in Egypt.

Hassan Ali, Chair of the Mass Communication Department at El Minya University, believes that the industry in the near future needs to establish a mechanism that is specifically tasked with protecting the media consumer.

He pointed to the establishment of an organization in 2011 – the Audience Protection Organization – which would ultimately raise the standard of media output.

“The audience should be granted the right of knowing the true information and be protected from the ongoing spread of rumors,” Ali previously told The Caravan.

In the meantime, Egypt is likely to remain one of the few countries in 2030 where print journalism continues to enjoy a large readership.

“The written word always has its magic and print allows you to save those words and keep them,” AbdelSalam says.

She projects that some TV satellite channels may lose their viewers, eventually closing down due to lack of advertising, but that radio will grow in accessibility and popularity.