Will the Ethiopian Grand Dam Secure Egypt’s Future Water Needs?

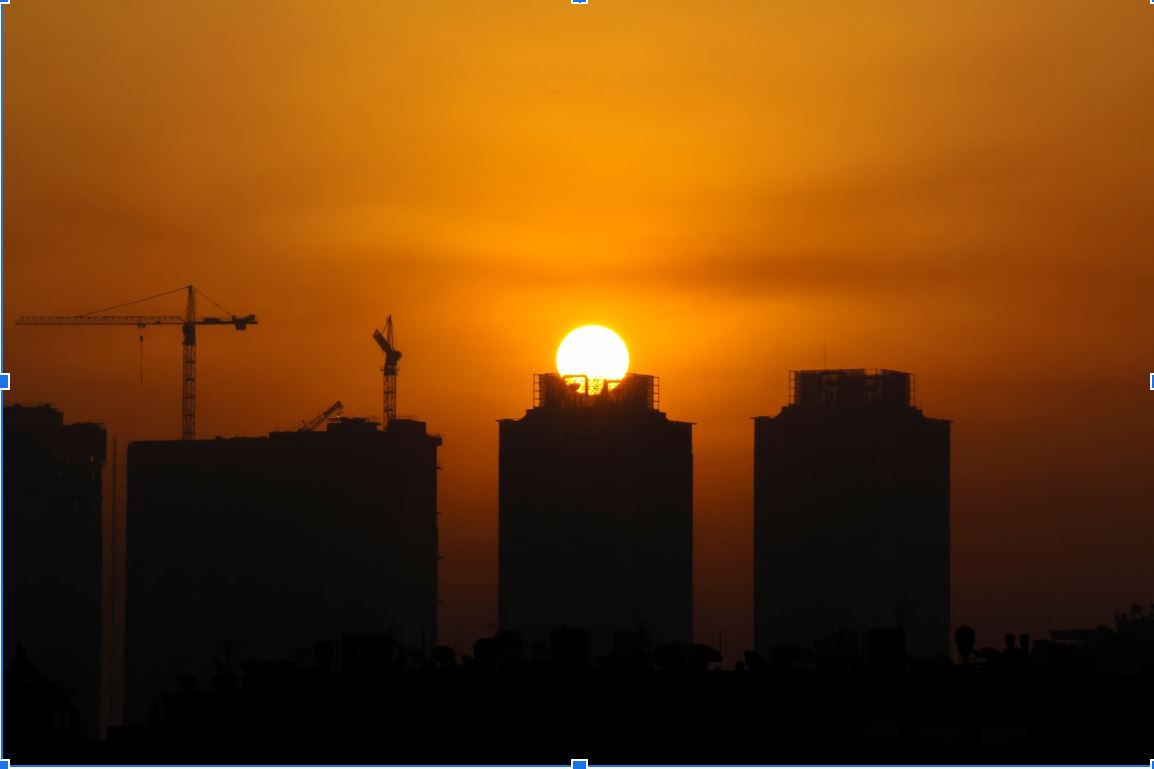

![Tutwiler said that Egypt has a water shortage problem, which has only been getting worse with population growth [Tamer Hegab]](http://www.auccaravan.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/IMG_9961_2-copy-e1431280336191.jpg)

[Tamer Hegab]

In 2010, five countries that share the Nile river basin moved to revise the colonial-era treaties (1929) that not only allocate the bulk of the river’s water to Egypt but also, allow Cairo to veto upstream dam projects.

But African nations, which have gained independence from colonialism in the past six decades and have undergone population growth, say the treaties needs revising.

They have taken initiatives to build several dams along the Nile, including one mega dam dubbed the Grand Ethiopia Renaissance Dam (GERD).

Estimated to cost $4.8 billion and generate 5250 MW of electricity, the dam – Egyptians had feared – would threaten their country’s only substantial water resource in the region.

According to press reports before 2011, Cairo and Addis Ababa had strained relations and no headway had been made to secure guarantees GERD would not diminish Egypt’s Nile water access.

Since 2013, however, Egyptian diplomats have regularly met with their Ethiopian counterparts to etch out a framework agreement about the damn.

On March 23, the two countries and Sudan signed the GERD preliminary agreement.

The three countries primarily agreed to the “fair use of waters and not to damage the interests of other states by using the waters.”

The agreement also included mechanisms for the peaceful settlement of disputes, transparency surrounding the dam’s operation policies, and development and research.

Ethiopia says the dam is being built to improve its economic development by becoming an electricity provider on a planned east Africa power grid, as well as solving their own electrical shortages.

Tensions … and benefits

When Ethiopia initially started the dam’s construction in 2011, Egyptian officials voiced fears that it would limit the flow of the Nile into Egypt.

During a speech in June 2013, former President Mohamed Morsi said that Egypt did not want war with Ethiopia but would keep “all options open” if the two countries did not reach an agreement that safeguarded Cairo’s rights over the Nile River.

Despite Cairo’s skepticism, Ethiopia said the dam would not negatively impact Egypt.

Ethiopian officials also said that GERD could benefit Sudan and Egypt by ebbing floods, maintaining a uniform flow of water all year round, and enhancing water management.

According to A Rebuttal of Statement made by Group of the Nile Basin (GNB) of Cairo University in 2013, uniform flow means “flood protection, irrigation expansion, water use efficiency, sediment load reduction, affordable clean power trade and an energy production uplift.”

Richard Tutwiler, director of AUC’s Research Institute for a Sustainable Environment (RISE), told The Caravan that, “it should also be remembered that there are now three dams in Sudan located between the GERD and

Egypt, and these dams already have an impact on Egypt’s water flow.”

Tensions between Sudan and Egypt have also been ongoing for decades. In 1992, Khartoum refused to cooperate with the Nile Waters Technical Organization and threatened to ignore the 1959 Nile Waters Agreement between the two countries.

The 1959 agreement “sought to regulate the use of Nile waters to ensure its optimal utilization in accordance with the provisions of international law.”

Sudan violated the agreement by not informing Egypt of its projects on Kenana and Rahaq canals.

Water Problems

Egypt has always maintained that the GERD and other such dam projects run counter to its strategic interests: any restriction on water flow downstream to Cairo could destroy agriculture and threaten the welfare of the population.

“Egypt is downstream from the principal source of Nile water, which is Ethiopia. Egypt is presently receiving about 55-60 billion cubic meters of water per year, depending on how much it rains in Ethiopia,” said Tutwiler.

Being very far downstream from the source means Egypt receives less water naturally than Ethiopia and Sudan, respectively.

Egypt already has a water shortage problem, which has only been getting worse with population growth.

Tutwiler said that “since the population continues to grow and the amount of water available is limited, the per person amount available each year will inevitably decrease, unless we find a solution.”

However, the major concern at the moment is how long it will take to fill the reservoir behind the GERD, which will limit Egypt’s water flow.

The reservoir will store water in case of shortages but also needs to be full to capacity in order for the dam to start working.

“Since the GERD is designed as a hydro-power dam, the dam will not function properly unless the water behind the dam in the reservoir is released to create electricity,” added Tutwiler.

Sharobeem El Masry, the director of water resources in Luxor – a local subsection for the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation, said the country will experience a temporary water shortage, due to the dam needing to be filled before the hydraulics (water powered turbines and mechanisms) can begin to work.

“If the filling is done in three years, then 24 billion cubic meters of water, which should have gone to Egypt and Sudan, will be retained in the reservoir. It could, however, take longer than that to fill,” El Masry said.

“The normal average annual flow to both Egypt and Sudan is 84.5 billion cubic meters of water, with Egypt’s share equal 55.5 billion,” he told The Caravan.

According to Emad Imam, professor of hydraulics and water resources engineering, there are also secondary problems that will be experienced in the long run.

“It is the evaporation and seepage losses from the reservoir which is estimated to be 2 billion cubic meters every year,” Imam said.

Annual evaporation losses from the High Aswan Dam (HAD) are 10-15 billion cubic meters by comparison, with GERD making up its unavoidable evaporation losses.

The GNB at Cairo University said that GERD water saving comes from “preventing flooding during high flood seasons, seepage or dumping water to the desert through spillways. The storage brings over 5-10 percent saving of water in the system.”

Effects on Agriculture

El Masry also warned that areas which require significant irrigation water for agriculture, such as Luxor, Qena and Sinai, may experience the effects of the shortage more than other parts of the country.

They will likely suffer losses due to bad crops and dehydrated fields.

Samir Makary, a professor of agricultural economics, believes that Egypt’s agricultural sector currently suffers from severe shortage of water.

“Egypt will be forced to give up agricultural production by 2030 if new sources of water are not developed. The real problem is not just the sufficiency of the dam; it is indeed, the shortage of water,” Makary said.

“The cost of water will be increased, to the extent that agricultural products in Egypt will not be competitive and farmers will have to give up agricultural production,” he added.

Exacerbating the situation is that Ethiopia’s strategies to fill the reservoir with water could be modified if downstream countries have dry (drought) years in terms of rainfall and water input.

But Egypt already has contingency plans in place should other countries upstream experience a shortage of water or a drought.

“The High Aswan Dam, with over 130 billion cubic meters live storage, is designed to sustain two years water needs in Egypt without having any inflow,” said the GNB.

Effects on Environment

The areas around the dam may also suffer environmental damage, and may cause problems for people living close by.

“The GERD has a large reservoir area, and that area will become flooded. Any people and animals living there will have to relocate, and any plants will be inundated,” Tutwiler said.

But Tutwiler also said that the Egyptian government is putting into place programs and strategies to combat these pressing issues.

The government could implement mechanisms to reduce water loss, increase water usage efficiency, and promote water reuse and recycling.

“The Ministry of Irrigation is highly concerned with this issue and other sources of water should be developed, one of which is desalination,” El Masry said.

Desalination is the process of removing dissolved salts from water, thus producing fresh water

from seawater to use as drinking water or for irrigation, according to the Oxford Dictionary.

“Studies in this respect will be made to reduce the cost of desalination, and further investigations into underground water sources are being explored,” added El Masry.

Research and Programs

Khaled Waseef, a spokesperson for the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation, says that there are three points of focus that the ministry will use to help conserve and utilize water.

“The first [is] maximizing the use of available water resources through the modernization of irrigation and land settlement, reducing the cultivation of sugar cane [which consumes much irrigation water] and the provision of new strains of rice, expanding the use of groundwater and reusing agricultural drainage water and wastewater,” said Waseef.

Growing less sugar cane and rice, considered to be staple foods, could save a significant amount of water.

The second course of action involves “maintaining water quality and preventing pollution, applying the laws protecting the Nile and raising awareness of the importance of water, [conservation],” Waseef added.

The final section focuses on “water resource development in cooperation with the Nile Basin countries” which will strengthen political ties, increase research, and achieve faster results.

Benefits to Egypt

There are a number of counterarguments that propose that Egypt will benefit from the GERD’s completion.

In the past, Egypt has been forced to divert excess floodwater and spillage to the Toshka desert valley to avoid flooding over the High Aswan Dam, which could be disastrous for major cities.

“System storage increase due to GERD will provide buffer storage and a new additional source of water above the HAD capacity,” said the GNB.

This means that rather than having to divert the spillage elsewhere, it could potentially be stored in the GERD’s reservoir and later put to good use.

GERD storage could also help decrease the amount of High Aswan Dam’s evaporation loss, thereby saving Egypt water.

Furthermore, GNB says: “[The] HAD’s design life will extend by more than a century due to GERD as more than 50 percent of the sediment build up at Aswan is estimated to originate from the Nile.”

GERD is also projected to create 12,000 jobs in Ethiopia and generate cheap electricity to countries as far away from the Nile basin as South Africa and Morocco.

The GERD project is expected to be completed by 2017.