Does the Egyptian Film Industry Demean and Objectify Women?

“Sexual harassment has become an art form for men,” says one film director.

BY AMIRA SHERIF

Ever since video of throngs of men chasing women in downtown Cairo’s Talaat Harb Square was published online in 2006, critical debate has focused on the issue of sexual harassment.

But since the January 25, 2011 uprising, stories of female journalists, women protesters and passers-by who were sexually harassed dramatically increased and made daily news headlines.

Initially, the incidents were seen as a disheartening stain on the euphoria generated from the promise of political change.

However, the public came to view sexual harassment as a component of the violence and oppression that has emerged in recent months and after the revolution.

It has been debated what kind of role the entertainment industry has had on sexual harassment incidents in Egypt.

Some claim that Egyptian film and music have social acceptance of such behavior, while others believe that the industry can help educate and raise awareness of a social malaise that has resulted in 99.3 percent of women being harassed, according to UN estimates.

Although it was released in 2010, director Mohammed Diab’s 678 falls into the latter category as it helped bring what was once a taboo subject into the forefront.

Despite its release before the uprising, Diab’s film – and the manner in which it addresses sexual harassment – remains as pertinent as ever.

The film documents the lives of three women from diverse backgrounds and social classes who – as victims of sexual harassment and assault – come together to combat the problem; it is based on true events.

In 2008, young filmmaker Noha Roushdy was walking home in daylight when a truck driver pulled up next to her and groped her breasts so violently that she fell to the ground nearly knocked unconscious.

The driver, Sherif Gomaa, then got back into his truck and drove off.

As fate would have it, the truck was forced to stop due to a traffic jam a few meters down the road. Roushdy caught up with the truck, pulled the driver out of his seat and attempted to take him to a police station.

As Gomaa began shouting, a crowd gathered and tried to break him free, accusing Roushdy of being in the wrong, blaming her for being amid men and other refrains which have only worked to harden the social stigma preventing women from holding their harassers accountable.

With the help of her friend Hind, who was with her at the time and witnessed the entire melee, and a stranger on the street, Roushdy managed to drive Gomaa to a police station, file a complaint and take him to court.

In what became a landmark case that proves the courts can and will convict sexual harassers, Gomaa was handed a three-year hard labor sentence.

Diab told the Caravan it was Roushdy’s courage and strength that inspired him to take a harder look at the issue of sexual harassment and write a screenplay that would hopefully educate Egyptian society.

He also explained that the film was an apology to all women, because he said that men who do not harass have no idea about the problem, because in their circles, the women who get violated never speak up.

“Many Egyptian men take it very lightly until it hits them personally,” Diab said in previously published media reports in 2011.

“Fifty percent of Egyptian men think this [sexual harassment] is a complete fabrication. This is a real problem that needs to be solved,” he told US broadcaster PBS.

Where Egyptian society stood on the matter of sexual harassment became abundantly clear when the film was released.

Although the film received mixed reviews, Diab was hit with two lawsuits and the threat of another.

One lawsuit alleged that Diab exaggerated the problem of sexual harassment and was smearing Egypt’s image; the other sought to prevent Diab’s film from being shown abroad.

Popular singer Tamer Hosny threatened to file a lawsuit because one of his songs was used as a background track while one of the film’s stars was sexually assaulted on a crowded bus.

Hosny said he was angered because the song has no correlation to the film’s theme.

Diab, however, says that sexual malfeasance is implied in Hosny’s lyrics and music videos, many of which influence young men.

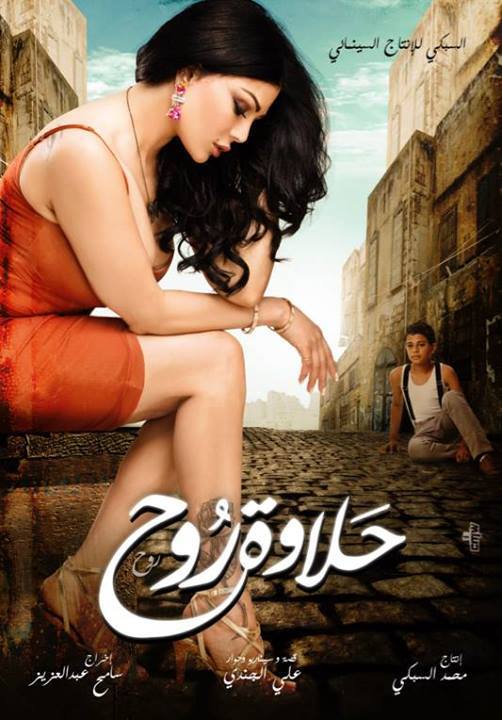

The latest film to court controversy for its capacity to influence young men to denigrate women and then sexually harass them is Halawet Roh (Sweetness of Roh), which was released on April 3 and then removed from distribution by government decree a few days later.

In the film, leading actress and pop star Haifa Wahbe commands a pseudo-erotic presence on the screen; donning what Egyptian conservative society would classify as provocative clothing, she prances about the street enticing and seducing a jaw-dropped male entourage.

“Halawet Roh is the worst movie of the year and a movie about a sexually repressed character that is designed to be seen by a sexually repressed society. But I am still against removing or banning the movie,” said film critic Joseph Fahim.

The film – with scenes of a young boy’s infatuation with Wahbe’s character, which leads to sexual harassment – drew such harsh criticism that it led to the unprecedented intervention by Egypt’s Prime Minister to order its removal, pending further review.

Egypt’s National Council for Childhood and Motherhood praised the Prime Minister’s move to suspend the movie, saying the film posed “a moral danger” which could impact “public morals negatively”.

According to media reports, Karim al-Abnoudi, the young boy appearing with Wahbe, has been reportedly harassed in the street by people angered by the film.

But Mahmoud El Lozy, actor and theater professor and director at the American University in Cairo, believes that the main cause of sexual harassment lies elsewhere.

“Religion has a main role in what we have reached nowadays and the oppression that we are facing,” said El Lozy.

The way that women are portrayed by Islamist narratives is the main reason for this state of oppression, he adds.

“Sexual harassment has become an art form for men,” said Lozy.

He believes that ultimately the “entertainment industry is a reflection of the society”, and if the society wants these types of movies then we are facing a problem of the society itself and not the filmmakers or producers alone.