Apathy Leading to Death, Detention

By: Mariam Mohsen

When people discuss crises throughout Egypt, they tend to focus on somewhat “mainstream” topics such as political affiliations; and demonize those they do not belong to, the media; and harshly criticize whichever channels portray opinions contrary to their own, traffic; and blame every vehicle in the street other than theirs and pollution; expressing disgust at the amount of garbage in the street on the basis that they do not litter.

If I were to analyze Egypt in terms of “crises,” I would focus on one: reading. We hardly ever read. We let our emotions guide us in all things; ranging from politics to academics. The crisis here is that our lack of interest in educating ourselves affects our country as a whole.

A basic example is the approval of military trials for civilians in the 50-member panel, which was tasked with drafting the Egyptian constitution.

Article 198 of the draft says, “Civilians shall not stand trial before military courts except for crimes that harm the Armed Forces.” Additionally, the rulings that come out of military trials cannot be appealed; a judge makes one ruling and that’s it for whatever case.

The vagueness of the Article baffles me. What exactly do those crimes entail? If, for example, a citizen protests against the Armed Forces, would that be considered a “crime?”

That was a rhetorical question; it would be considered a crime. Earlier this year, an AUC student named Abdallah Hamdy was detained in October after taking part in an anti-Coup demonstration.

Also, his detention came before the adoption of Article 198, which leaves me to wonder the extent to which people’s liberties will be limited once it is actually applied.

How many AUCians know the details of this law and its consequences? Better yet, how many of them know that one of their colleagues has been detained for the past two months?

Let me rephrase my questions; had AUCians read about the details of military trials and the effects of it and known that they have a detained colleague, would they have been this silent about it?

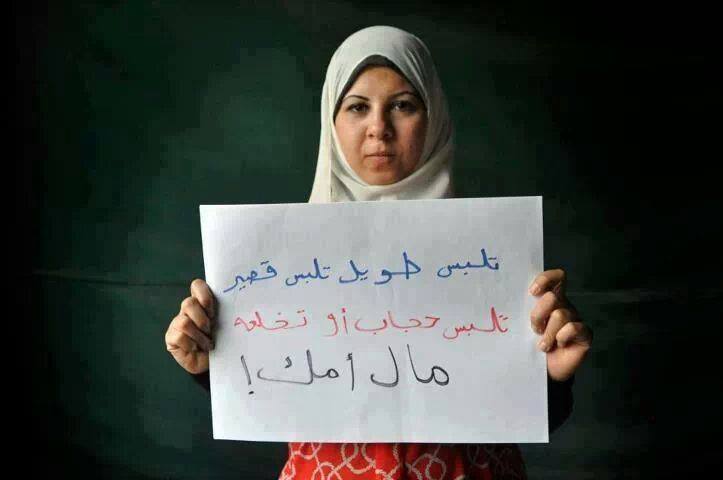

Another example is the newly imposed protest law. I would bet that if AUCians comprehend what this law entails, their current state of apathy would be completely different.

In accordance to the law, police forces are present in all protests in order to ensure citizens’ safety and security. Furthermore, Article 11 dictates that forces are permitted to disperse any protests where they deem any actions as unlawful or non-peaceful.

The following two articles explain the means through which those dispersals take place; demonstrators should be given a verbal warning; if they do not respond to the warning, forces are permitted to use gradual force, which includes water batons, teargas, rubber bullets and birdshots.

The latter means that if students hold a protest at AUC against the government, for example, and they carry out any actions that are perceived by police as contrary to the law, the police may disperse the demonstration through the before-mentioned measures. Now, it may seem as though nothing like this would actually be imposed on any university grounds. However, it already has.

A student named Mohamed Reda died during police force’s dispersal of a protest at Cairo University against the protest law. In accordance to the law, the same thing could be applied at our university, and even worse, can be justified by law.

If the members of our community had known of the magnitude the protest law could have on them and the freedoms AUC grants them, would there have been tens of students in the “For Justice We Stand” protest against police brutality, or would they have been hundreds – at least?