The Last Black Man in San Francisco: Tales From the Ever Changing City

By: Hanya Captan

@HanyaCaptan

Following the dot com boom of the 1990s which brought with it an influx of skilled tech workers to the city, longtime San Francisco residents have been subjected to relentless urban displacement.

In a city inhabited by a billionaire population that includes Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg and Google’s co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, it is also a city with more homeless people than any other in the U.S.

As tensions continue to mount between working class communities and renters seeking to price them out, The Last Black Man in San Francisco (2019) offers a refreshing take on the issue from the perspective of San Francisco natives Joe Talbot (director) and Jimmie Fails (star).

The film was screened as part of the American Studies Film Series, a monthly series organized by Assistant Director from the Center of American Studies and Research (CASAR) Yasmeen El Ghazaly and Assistant Professor from the department of English and Comparative Literature Balthazar Beckett.

Before coming to AUC, Beckett taught at UC Berkeley, San Francisco State University and at San Quentin State Prison in the Bay Area.

“The film makes visible and engages a long list of social issues that determine life in the Bay Area today. Among them are San Francisco’s hyper-gentrification, long-standing social and racial inequities…environmental racism, and, above all, the ethical question who this city belongs to,” Beckett said.

The film tells the story of Jimmie Fails – playing here a fictionalized version of himself – as he attempts to reclaim his childhood home in the since gentrified Fillmore District. At the beginning of the film, Fails resides in Bayview-Hunters Point with his best friend, Mont, played by Jonathan Majors, and Mont’s grandfather, played by Danny Glover.

The choice of Bayview-Hunters Point for locale is notable due to the area’s extensive history of radioactive contamination. A community composed of predominantly Black residents, its economic peak came from the area’s shipyards in the lead up to World War II.

Shipyard workers and the surrounding land were exposed to this toxic radioactivity when ships that were exposed to radioactive testing in the Pacific would be returned to the shipyards to get washed down.

These naval shipyards have long since been abandoned, taking with them one of the area’s main sources of employment. The harmful radioactive material still remains and continues to be a source of scandal for the area.

Beckett explained that the film depicts this issue of environmental racism in the opening scene, which features men in biohazard suits cleaning an area where Black children are playing.

The environmental racism which Beckett describes, is only one facet of the rampant social and racial inequity that taints San Francisco.

“Because the face of tech wealth and of gentrification is often white, the percentage of Black San Franciscans has diminished from close to 14 percent in 1970 to around 5 percent today. And a whopping 37 percent of the city’s unhoused population is Black,” Beckett said.

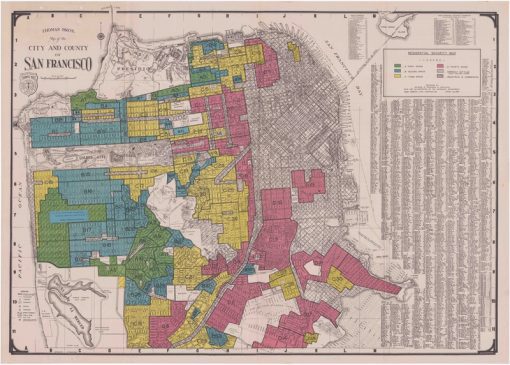

To establish the city’s history of racially motivated housing discrimination, Beckett preceded the screening with a short presentation explaining how government redlining maps perpetuated racial segregation in San Francisco.

Redlining, as defined by Britanica, refers to the “illegal discriminatory practice in which a mortgage lender denies loans or an insurance provider restricts services to certain areas of a community, often because of the racial characteristics of the applicant’s neighbourhood.”

This practice largely informed the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), an initiative established by Congress in 1933 to help combat widespread urban foreclosure following the Great Depression.

This initiative would issue homeowners low interest, long-term loans which lead to the desired spike in home-ownership. However, these loans were not distributed to all people.

In order to determine which areas would be safe investments, HOLC created “residential safety maps”, which were compilations of local data gathered from cities across the U.S.

“Neighborhoods were classified into one of four categories based on ‘favorable’ and ‘detrimental’ influences. Factors included terrain and type and age of buildings, as well as the threat of infiltration of foreign-born, negro, or lower grade population,” as explained by Northern California media website KQED.

Though the future Fair Housing Act of 1968 would prohibit this form of housing discrimination, the foundations for which communities could inhabit which neighbourhoods had already been established, to this day, African American lenders continue to receive worse terms for mortgages than white lenders.

All these race-based housing issues prompted countless resistance movements intended to raise awareness and counteract recent waves of gentrification.

“San Francisco has a long history of anti-eviction protests and housing rights activism…More recently, in May of 2020, Reclaim SF, a group of unhoused women briefly occupied an empty building in San Francisco’s Castro district,” explained Beckett.

The film depicts this local resistance to gentrification in Fails’ fight to reclaim his childhood home. Located in the Fillmore District, a neighbourhood with a rich history of ethnic diversity, Fails’ family lived in the Victorian home until they were forced to leave it.

Now inhabited by a white couple, Fails remains fixated on the house and regularly visits it to perform basic maintenance activities – much to the wife’s dismay.

When the couple are forced to move out due to a legal battle with the wife’s sister over the property, Mont and Fails take up residence in the vacant home.

“In the years that I have lived here, I have seen many working-class friends, colleagues, and students leave the city because of rising rents,” Beckett said.