Battling for Memory and Narrative

By: Maya Abouelnasr

@EmEn1125

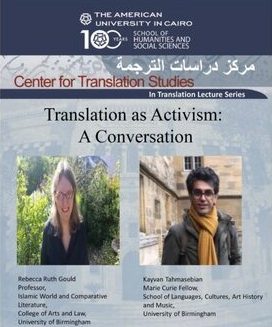

Photo: Poster of the webinar

In a world that is increasingly struggling with populism and authoritarianism, translational activism becomes all the more important as it engages in battles of memory and narratives against these constructs, and produces social change by providing alternative accounts of history.

Poet, critic and Marie Curie Fellow at the University of Birmingham Kayvan Tamasebian emphasized the multiple dynamics of translational activism, which seeks to ultimately assess the potential of translation in yielding social and attitudinal change.

In the “Translation as Activism: A Conversation” webinar, Tahmasebian first distinguished between political engagement and social activism. There are different perspectives through which the field can be defined and examined.

Translational activism can be viewed through the political lens and framing of power. It can also be viewed through the activist perspective of counteraction and resistance that is meant to challenge dominant power structures.

“I think this difference between political engagement and social activism should be emphasized [to understand] the dangers of activist causes degrading into name games of position taking or political lobbying,” Tahmasebian said.

Tahmasebiaan emphasized that understanding the difference between politics and activism is especially crucial to achieving the goal of the translational activism field.

He explained how activism can be perceived as a speech act that has the capability to evoke powerful emotions and foster social change.

Translational activists then engage in a battle of memory to maintain the narrative change against those in power who wish to keep firm control over collective consciousness and forgetfulness, using various tactics such as censorship.

In addition to combatting the battle of memory and being a speech act, translational activism, in providing alternative narratives, challenges dominant institutionalized ones to fight in a battle of opposing narratives.

Regulators and media gatekeepers, through censorship and manipulating social memory, engage in these battles to delay the timeliness and impact of activist content that is not in alignment with mainstream, dominant narratives.

Tahmasebian added that it is important to acknowledge that there is a danger of institutionalizing activism.

“Not every activist intervention is funded and they [activists] are being used as a kind of a data for power to consolidate itself,” Tahmasebian told The Caravan.

Tahmasebian further commented on how some academic analyses of activism and translation consequently look to exploit the use of activist engagement simply for monetary gain, rather than for social change.

Rebecca Ruth Gould, professor of Islamic World and Comparative Literature at the University of Birmingham, also commented on the importance of timeliness in activism and how it combats the battle of memory through raising consciousness.

She emphasized that, even though activism may be future-oriented, the past is not incidental. The knowledge of the past plays a significant role in allowing present day translators and activists to work on accomplishing what past generations could not.

Gould further pointed to language being an archive of memories and how translators are responsible for keeping these non-dominant, non-mainstream collective narratives and memories alive. This has nowadays been aided by the digital circulation of books helping bypass political barriers.

She added the process of working to keep certain memories and narratives alive can still be disrupted by dominant forces’ control of social memory and narratives, as well as through rejecting publication of these issues.

Gould believes that the most harmful outcome of the armchair approach of analysis, that is often employed in academia when synthesizing past information and schemas, rather than expanding on discourse, is deciding not to translate at all.

“There are bad translations; there are inadequate translations. Translations always have problems, but I think to not do it all, whether you’re an academic or a non-academic, then you’re really bringing it all to an end,” Gould told The Caravan.

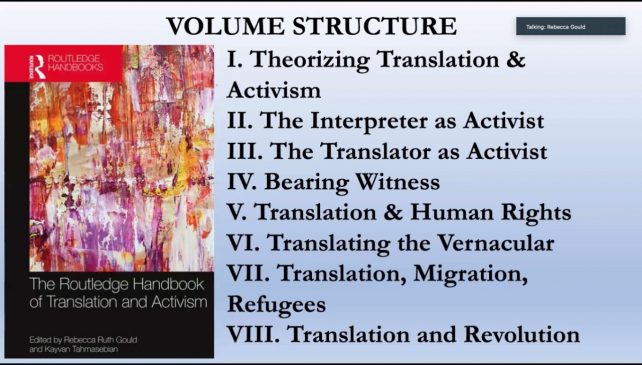

Gould and Tamasebian co-edited and published The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Activism in June 2020.

According to Professor and Director of the Center for Translation Studies Samia Mehrez, the handbook features activist voices from all over the world that expand exposure to global narratives.

“Their volume on translation and activism provides a staggering number of much needed and, in many instances, underrepresented voices […] that question, settle and reassess the interrelated connections between translation and activism in a globalized world,” Mehrez said.

Bushra Hashem, an attendee and a dual degree Comparative Literature and Islamic Studies graduate student, said that her biggest takeaway from the talk was how the timeliness of translations’ publication affects collective cultural memory and relates to political agendas.

Hashem added that this is especially relevant in the case of indigenous literature and culture.

“Cultural preservation of these literatures and texts is not a priority in the market. We could even say that there are agendas to ‘forget’ these narratives,” Hashem told The Caravan.

The late October webinar was part of the Center for Translation Studies’ In Translation Lectures series in which the translations of an array of different texts, such as Ancient Egyptian texts, are presented and analyzed by field experts.